translated and summarized by: Liz Wollner-Grandville,

English summaries June 1 - 12

Venice Biennial

54. Venice Biennial - Markus Schinwald

04.06.11 – 27.11.11

Gesamtkunstwerk of Identity Analysis

Direct view into the Austrian Pavilion as well as its entrance is blocked, only a narrow opening in a wall, set up in front of the entrance, allows for any insight. A methodological principal that Markus Schinwald culminates in a profound point by means of his architectural intrusions and installations, picturesque as well as cinematic moments with corresponding and convincing aesthetics. Evident detours from the conventional, irritations in every respect - yet understanding and perspective by undermining conventional premises and hierarchies are the key factors. They determine Schinwald’s context of perceiving art, architecture and human existence and define the pavilion in its complex entirety - with alternative legitimacy.

Schinwald broke with the sublime splendour of the interior of the historical building in a sophisticated and sensitive manner. A labyrinth welcomes those entering - with white walls hanging from above. Both the view and the paths are blocked to the centre of the body, yet the free space thereunder is distinctly present and perceivable. Through bending down one can see the entire room and the legs of others walking around the pavilion – an amusing change of perspective and a theoretical epitome of undermining the structure determined from above.

The entire pavilion is penetrated by a spherical sound-world, originating from videos positioned at the endpoints of both side wings and creating a slipstream effect. By way of detours, the visitors are guided over architectural incisions and fractures, which create unexpected insights and open views on misleading picturesque and sculptural moments.

Sculptures made of table legs are mounted on the walls like objects. Associatively brought to life they nestle or cling to an edge near the ceiling, hang on a rod or from a hook. They present both a formal as well as a contextual analogy to the interventions of 19th century paintings: Schinwald retouched the portraits with constructions made of linen, chains or leather, which he wrapped around parts of head or face. It is these interventions, which he describes as prosthesis, that impair or stimulate the physical world of senses of those portrayed – in any case they irritate the visitors. Psychological inner worlds seem to surface mysteriously, at least have an effect of uncertainty, but then the uneasiness, which comes up at first, is erased by irony, which reveals itself upon closer deliberation, and transforms itself to serene, ambiguous attention.

The same process takes place watching the videos, which form the final accord of the course. The solemn cathedral-like atmosphere, which dominates the entire pavilion, is created by organ-like sounds and the silent attention triggered by the buzz of voices accompanying the videos. Alternating, a female and a male voice recite prosaic texts that are only partially comprehensible. The fragmentary also characterizes the cinematic work: Schinwald chose a rundown brewery as the location. The detailed takes of the decrepit empty rooms lift the cool clarity of the architectural forms like the perceivable fragmentary parts of the scenery’s history. Abysses are at the same time perspectives; stairs and openings in the wall are precise meaningful parts. It is the congruent stage for the actions of an individual or a number of protagonists, which presents cinematic segments without any time sequence, phrases of an emotional discourse. The abstract choreography, the quiet artificial gestures and motions resemble rituals, which, like metaphorical moments, circle around topics of autonomy and state, irrational depths of individual and collective existence, physicality and sexuality, congruent to the acoustically audible content. Oppressive moments arise, put in perspective, infiltrated and dissolved by subtle ambiguity and aesthetics.

Marcus Schinwald formed Josef Hoffmann’s pavilion as an immersive artificial cosmos in which irritating and stimulating factors are intertwined to a sensual entirety, which articulates itself both mysteriously and at the same time precisely and with a high standard of aesthetics. The experience switches from uncertainty to subversive amusement; pathos and irony penetrate one another. The young artist created a very stimulating Gesamtkunstwerk at the Venetian Giardini and thereby, if he did not – as Claudia Schmied, Minister for Cultural Affairs said – define the Austrian identity, then at least he did not miss the point and artistically epitomized some facets.

By Margareta Sandhofer

La Biennale di Venezia

30122 Venezia, Giardini della Biennale

www.labiennale.org

Opening hours: daily from 10 a.m. – 6 p.m., closed on Mondays

Venice Biennial

54th Venice Biennial – ILLUMInazioni – ILLUMInations

04.06.11 – 27.11.11

All signs point to the future

At the two locations of the Venice Biennial there are two venues that are more prominent than others: the first room in the Arsenale and the large hall in the big pavilion. This year's Biennial, curated by Bice Curiger, presents both rooms in contrast to one another: Song Dong blocks the generous space with a labyrinth of cloakroom doors at the Arsenale. In contrast, the Padiglione is opened by three (unfortunately badly presented) Tintorettos, which are meant to introduce the main theme “ILUMInazioni – ILLUMInations”. While Song Dong’s Para-Pavilion, which accommodates works by his colleagues, articulates a state of encryption, of obstructed view, of difficult access, Tintoretto’s paintings symbolize brightness, opening, and simultaneously, dramatically overwhelms the audience.

This contrastive pair turns out to be a meaningful bracket for the works of the other 81 artists. Despite Curiger’s title, numerous works represent the opposite: the obscure, mysterious, encrypted, surreal: like the mysterious film by Nathaniel Mellors, who lets an odd family resort to questionably motivated actions; or the work by Emily Wardill in which glamorously dressed protagonists recite works by John Ruskin behind Gothic glass windows. The object photography by Annette Kelm and Elad Lassry are difficult to decipher; and Franz West’s Para-Pavilion, fitted with works by Gelitin, Octavian Trautmannsdorff, Roland Kollnitz and numerous others fosters an orderly chaos in an unconventional hybrid of private accommodation and public gallery display.

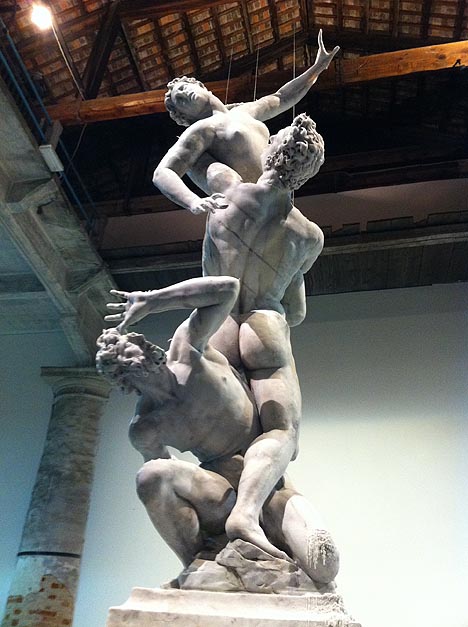

At the other end of this scale you will find works that devote themselves to light – such as Philippe Parreno’s blinking and rather banal light bulbs, James Turrell’s adequately known light room, Haroon Mirza’s electric installations - at times accompanied by unpleasant sounds, or Urs Fischer’s candles, gently burning down in the form of a Raptus group by Giambologna, his office chair or the artist Rudolf Stingel, which, in the end, will have all melted to a heap of wax.

Extremely gratifying is the large percentage of promising young positions (by - in addition to those already mentioned: Ida Ekbland, Rashid Johnson, Cyprien Gaillard or Mohamed Bourouissa), and, in contrast, almost disturbing, the not very exciting performance by established artists: except for Cindy Sherman, who successfully came up with a new invention, and David Goldblatt, whose documentations about rueful criminals takes on a successful synthesis with Monika Sosnowska’s Para-Pavilion, the Big Names were disappointing: Marizio Pavillon rehashes one of his earlier works by scattering pigeons throughout the pavilion, Monica Bonvicini’s stylish show-stairs in no way reflect the power of her earlier works, Fischli/Weiss designed a boring installation and Christopher Wool is no longer able to enthral anyone with his hundredth edition of paintings that imitate screen-prints.

That’s how the younger generation stole the show and, with this powerful signal, rejected any culture pessimism. No need to worry about a lack of young talent.

By Nina Schedlmayer

La Biennale di Venezia

30122 Venezia, Giardini della Biennale

www.labiennale.org

Opening hours: daily 10 a.m. – 6 p.m., closed on Mondays

Lenikus Collection

Studio 9

19.05.11 – 27.09.11

Dancing sculptures, kitschy landscape paintings

The dangers of group exhibitions can be manifold: ideally the individual positions complement each other, yet more often they threaten to group themselves to insignificant combinations - with a validity close to zero.

Curator Eva Maria Stadler, who was commissioned to organize an exhibition with 16 Studio-Program participants, approaches these risks in an offensive as well as nonchalant way. Since the works by the artists, who resided at the Lenikus Collection for three months as artists-in-residence, do not have a common denominator she leaves them their individuality. To do so, the walls on which the works are presented, were painted in different colours, thus offering each their own presentation background.

Each piece deals with different topics – ranging from the aesthetics of kitschy landscape paintings (Carsten Fock), the relationship between body and clothing (Anna Kirsten Krambeck), dance in sculpture (Kalin Lindenas), theatrical elements(Christodoulos Panayiotou), the course of time (Elizabeth McAlpine) or the history of Faber-Castell (Kathi Hofer). Despite the overall concept of leaving each work to its own, some pieces seem to charge each other: Nicola Brunnhuber’s cupboards covered with cellophane have an almost sensual effect in combination with Lucie Stahl’s scans, shrink-wrapped in polyurethane; and Alex Ruthner’s paintings are intensified by Björn Segschneider’s video installations, with their noisy earthquake simulations.

It becomes clear that the works have a high aesthetic standard and deal with their content in a serious way. Substance is present throughout the entire exhibition, yet here and there, the exhibition tends to be slightly tepid. A little more irony, a little more refraction and – ultimately –a little more political rebellion could have vivified the Lenikus program.

By Nina Schedlmayer

Sammlung Lenikus

1010 Vienna, Bauernmarkt 1

email: sammlung@samlunglenikus.at

www.sammlunglenikus.at

Hofmobiliendepot – Möbel Museum Wien

Marcel Breuer – Design and Architecture

16.03.11 – 03.07.11

Until it bursts

Vienna was not worth an episode; it was – as he described - the “most unhappy time of my life”. Only a few weeks after he joined the Academy of Fine Arts, 18 year-old Marcel Breuer, born 1902 in Pécs, Hungary – was drawn to the Weimarer Bauhaus where the next avant-garde was already very much alive.

Even if Johannes Itten attested the young student great talent as a painter, painting was simply too boring for Breuer. At first it was furniture, and later – and that was probably corresponded most to his self-conception – architecture. Walter Gropius became his teacher, mentor and lifelong (paternal) friend.

Design and architecture remain to be the two main themes for which Marcel Breuer (1902 – 1981) still stands today – for one he is known in Europe and for the other in the USA, where he emigrated in 1937. In the exhibition at the Hofmobilien Depot (organized by the Vitra Design Museum), numerous originals, documents and models present both topics, bringing up the question where aspiring for aspiration leads. The master cannot be denied a certain audacity in both fields; audacity, passion for new materials and a profound pleasure in surface structure.

Following the first wooden furniture designs, strongly influenced by the De Stijl group, it was a bicycle handlebar that inspired Breuer to employ steel tubes as the new material for his work - the result being the tubular steel furniture “Wassily”, which became a classic as well as his subsequent models known as the cantilever chairs. Yet, Breuer’s aluminium and laminated wooden chairs were not as successful – but that didn’t matter much in the USA – here everything centred on realty.

And again his work was characterized by audacity. “This is what one calls an experiment”, was the laconic comment to the Breuer’s minimalistic balcony design, which was only stabilized by steel cables and went down someday. An experiment, according to Breuer “was one of the responsibilities of an architect”, and beyond that he aspired towards typologies, clear forms that could be repeatedly utilised. Unique, if not spectacular, are Marcel Breuer’s monumental sacred buildings, e.g. St. John’s Abbey in Collegeville, Minnesota. Here it is less the audacity or experimenting that are impressive, but rather the sculptural quality of the outer shell and the overwhelming interior, a grandiose symbiosis of various surfaces and lighting.

Unhappy or not, Marcel Breuer’s 30th obit will be commemorated in Vienna - as an anecdote to the missing episode.

By Daniela Gregori

Hofmobiliendepot – Möbel Museum Wien

1070 Vienna, Mariahilfer Strasse 88, entrance Andreasgasse 7

Tel: +43 1 524 33 57 – 0

Fax: +43 1 524 33 57 – 666

Email: info@hofmobiliendepot.at

www.hofmobiliendepot.at

Mehr Texte von translated and summarized by: Liz Wollner-Grandville

Teilen

Teilen