translated and summarized by: Liz Wollner-Grandville,

English summary February 23 - March 1

Galerie Hubert Winter: Stephen Skidmore

Enthralling boredom

It could well be that visitors to Hubert Winter’s gallery will be caught yawning. At first sight, paintings of blurred facades, trees, and streets strike one as being rather boring.

But after taking a closer look at Stephen Skidmore’s seemingly old-fashioned paintings they are surprisingly appealing. All of the paintings of this exhibition, mainly created in different tones of brown and at times brightened up by a blue door or a red car, show the view from Skidmore’s studio window in West London, misted by rain on the windowpanes. Skidmore spent five years staring out the same window onto the same street and simply painted what he saw– sounds a bit like voluntary isolation, or obsession, but it also has a lot to do with being absolutely focussed and tenacious.

The windowpane, set between the eye and the view like a membrane, reveals different manifestations of rain – once as fine drops, once as arduously flowing streaks – and seems to set free as much as it transfigures.

Skidmore’s focus varies from painting to painting: a façade; an extract of the façade, hugely enlarged – an irritating moment. On some paintings a bare tree stands in the way, sometimes everything dissolves. But all of his paintings, which are devoid of people, all convey the feeling as if someone was on the search, but: for what? They tend to remind of Michelangelo Antionioni’s “Blow Up”, - the difference being that there is no crime to be detected in Skidmore’s paintings. Amazing, how exciting boring paintings can be.

Nina Schedlmayer

Galerie Hubert Winter

1070 Vienna, Breite Gasse 17, until 07.03.09

www.galeriewinter.at

Young Austrian Art: the4graces– Salon Greed

The old inwardness

For one, if a group of artists calls itself “the four graces” it immediately reminds of the photography performance gang “Die Damen” (the ladies) and for two, this again is so banal, that it sparks up interest.

It might be unfair to compare a 21st century group of female artists with one that was active in the 1980s. The comparison imposes itself – but it is flawed. While the relaxed self–staging of “Die Damen” pointed to sexism, the four graces withdraw into a not really new inwardness, characterized by the mood: sunny to overcast. “Salon Greed” shows paintings of women eating sushi, women with animals, women painting their toenails, women wearing fishnets and corsages, women with red sandals, women seen from the back, fun women, melancholic women, and interiors: pompous halls, hotel rooms, decorative corridors, delicately painted, some parts left white; all nice to look at and markedly harmless.

And the four graces come across as equally harmless in their video in which they do gymnastics accompanied by a blondie-song wearing transparent pink clothes and fooling around. Admittedly, their clumsy gymnastics in the garden and their parody of synchronised swimming in the small pool are somewhat amusing. However, their criticism of the body form – another one of these female topics – seems rather stale, as it was state-of-the-art in the 1970s.

The inflationary appearance of the female imagery obviously only serves to reflect on “being a woman”, both in general and in particular. Following the discourses of the last decades this is not rather insufficient.

Nina Schedlmayer

Young Austrian Art

1070 Vienna, Breitegasse 19, until 14.03.09

www.youngaustrianart.com

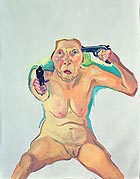

MUMOK Museum moderner Kunst: Maria Lassnig – The Ninth Decade

Lassnig forever

Maria Lassnig, who will turn 90 this year, is one of the few Austrian artists whose works are highly praised by curators, art historians, and critics. At some point Valie Export was in the same league, even if her earlier works were more disputed; the same was the case with Brus, Weibel, or Rühm.

After some intense discussions with Lassnig, Curator Wolfang Drechsler came up with a straightforward course through her work: at the entrance one will find her threefold-self portrait, showing the metamorphosis of an armless, fleshy creature, to a grotesque pseudo-being, developing into an to an anaemic, but obviously contemplative figure. A little further on are her works on sexual violence: the obese guy, leaning over a doll-like figure, and the other, holding the drawing of a woman paralysed by fear in front of his male privates.

It is rather daunting, how fear, pain and horror unite with subtle humour. Examples are her works “Nasenflucht in die Wasenschlucht”, the “Hochzeitsbild”, “Fotographie gegen die Malerei”, and the horribly maimed self-portrait “Eiserne Jungfrau und fleischige Jungfrau”. Among the most terrifying works is her self-potrait, in which she holds a gun to her forehead and one towards the onlooker. Rarely is panic and aggression so drastically expressed.

Just recently Lassnig tried out something new with her so-called “Cellar Paintings”. These works strike one as oddly modish, no wonder that Lassnig describes them as “unimportant”. But they prove that the artist, who does not want to be reminded of her age, but refers to it so often, is – even in her ninth decade – no where near stagnation.

Nina Schedlmayer

MUMOK Museum moderner Kunst

1070 Vienna, Museumsquartier, until 17.05.09

www.mumok.at

Liechtenstein Museum: On Gold Ground. Italian painting between Gothic tradition and the dawn of Renaissance

Why go into the blue?

The current exhibition at the Liechtenstein Museum offers a chance to learn about Gothic and Renaissance painting. The presentation offers a didactic part with an introduction to gold-ground painting and other details of this art, while another part of the show presents 50 works of Italian artists from the 14th, 15th and 16th century.

The Liechtenstein exhibition focuses on the period in which Italian art, mainly in Siena and Florence, were in the transition process from Gothic to Renaissance. At that time, Sienese painters were still working in a Byzantine style and added a golden background to their sacral paintings, while their rival Florentine colleagues were already in a transition phase: human figures were shown more realistically, positioned in a parallel and then in a central perspective. Nature was discovered as a newly staged background and was more appreciated than the shiny metal. But it was the Sienese artist Ambrogio Lorenzetti who painted the first realistic landscape.

Gold-ground paintings have been part of the Liechtenstein Collection since the time of Prince Johann II (1840/1858 – 1929), as well as the Academy of Fine Arts portrait gallery, but not in the Art History Museum’s “Imperial Collection”.

The pieces shown in this exhibition belong to partners of the Private Art Collections and the Paris-based Gallery Sarti. The audience is thereby offered the rare opportunity to compare top-quality panel paintings originating from a significant art historical era, and to put them into context with other objects, such as the gilded Cassoni (wedding chests), two Tondi by della Robbia and a variety of scriptures.

Maria-Gabriela Martinkowic

Liechtenstein Museum

1090 Vienna, Fürstengasse 1, until 14.04.09

www.liechtensteinmuseum.at

Mehr Texte von translated and summarized by: Liz Wollner-Grandville

Teilen

Teilen